Toothbrush abrasion, or other types of abrasion are relatively rare – but to see a more detailed treatment check out the Wikipedia article on dental abrasion. They also report on dental afraction – and provide copious references to the literature for your more detailed study.

Organization of this Chapter:

Basics

Nature of the Problem – Observations

Time Frame

Recurrent Lesions

Moving Lesions

Facial versus Lingual

Shapes

Causes of Non-carious Cervical Lesions

Treatment of Abfraction Lesions

Bottom Line for Noncarious Lesions

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Toothbrush Abrasion or Dental Abfraction: Basics

If you run your fingernail over the facial surface of your teeth toward the gingiva, as if you were trying to hook the border of the enamel , you have about a one third chance of finding a notch-like lesion on some tooth, particularly the premolars. The fingernail will catch at the sharp edge of the enamel as you bring it back toward the cusps. This is NOT the normal CEJ contour. These lesions most often appear on the premolars, but many patients show them to be quite pronounced on the incisors or canines, and sometimes they even show up on the lingual or palatal surfaces. Often, particularly in older patients, the lesions are very deep, threatening the pulp of the tooth, and weakening the tooth substantially, especially if there is an amalgam restoration (silver filling) in the occlusal surface.

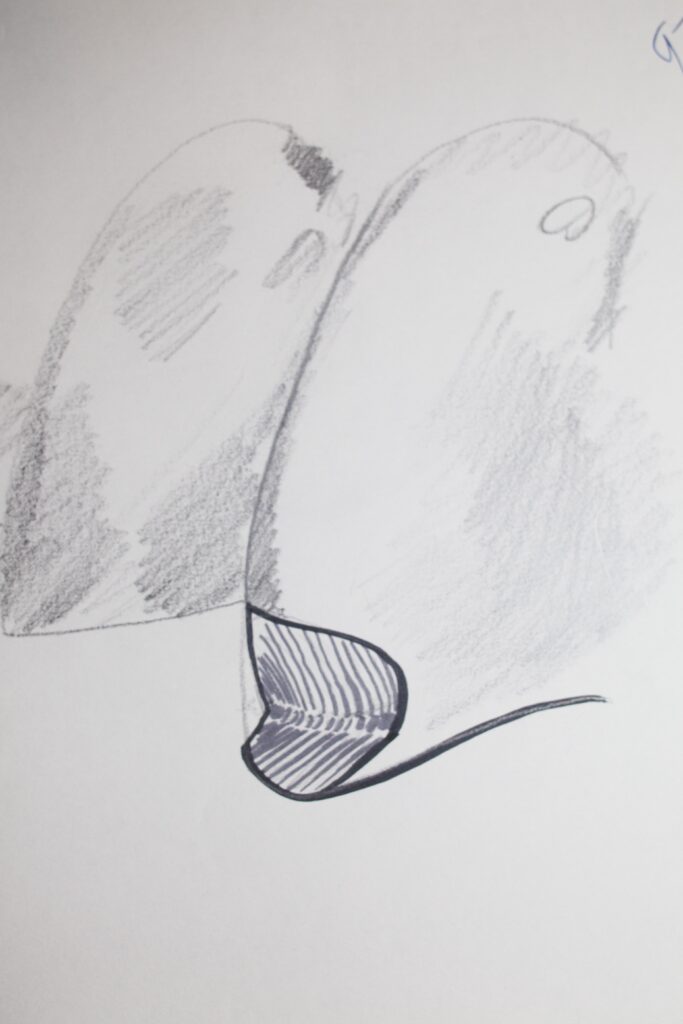

The photograph below shows lesions that we call “bowl-shaped”. This is to distinguish them from “wedge-shaped” lesions, which are far more common. First, what are these lesions called, and second what causes them? It is most important to realize that there has not always been general agreement in the dental community as to the cause, and therefore, there have been alternative theories. For decades the most common description heard was “toothbrush lesion”, or “toothbrush abrasion lesion”, or even “toothbrush erosion lesion”, or some other variant, always with the word “toothbrush” in there somewhere. The implication is that they are caused by improper brushing. In fact, generations of dentists all over the world have been trained to council patients with these lesions in more proper brushing techniques, whether the patient was displaying “bowl-shaped”, or “wedge-shaped” lesions.

In fact the lesions shown in the photograph above are “bowl-shaped” and MAY be due to toothbrush abrasion, but these are VERY rare. Some people back in the days of coarse toothpastes and hard brushes demonstrated a set of lesions that certainly SEEMED due to vigorous back-and-forth brushing, but there has been a historically trend to paint all such lesions with the same “brush”. This is particularly true because no one had an alternative hypothesis!

Since the 1970s, however, an alternative hypothesis has gained acceptance which suggests that the “wedge-shaped” lesions are due to excessive occlusal stress. So, which is the correct explanation in your case? It could be one, the other, or both answers – but by the end of this chapter you might be able to figure it our for yourself. And, determining the CAUSE is very important in directing the most appropriate treatment.

The Nature of the Problem

To have a name that doesn’t imply cause, let us simply call these lesions “cervical lesions”, demonstrating that they appear near the cervix or neck of the tooth. This implies that they are near the gingiva, but does not imply anything as to the cause. Often you will also hear the term “non-carious cervical lesions”, suggesting that the cause is definitely NOT due to a decay process. Of course, there CAN be lesions in the same location cause by decay or carious activity, but they are readily distinguished, as they involve soft, brown areas with clear whitish decalcification or demineralization around the edges. The picture below shows large CARIOUS cervical lesions, or those caused by decay.

We’ll proceed to look at a drawing and photograph that demonstrate some the basic appearance of these “wedge-shaped” lesions.

………. Time Frame

Non-carious cervical lesions take many years to form. Even in the most aggressive cases it must require at least 10 years before the lesion becomes obvious. This means that very few such lesions can be found on the young, but they are often found on middle aged patients. Elderly patients show them most commonly and they can be very deep, penetrating nearly half-way through the tooth!

There has been no study demonstrating the rate of lesion formation, but they have been shown definitely to correlate with age. The cause, then, is probably in effect over a long period of time, and works slowly. Why would cervical lesions appear so infrequently in patients prior to the thirties? We’ll try to answer this later, but there is precious little hard data to support any claims to complete understanding.

Also – there is a reason why in a typical elderly person the lesions would not get larger with time. This reason will be discussed a little later.

……… Recurrent Lesions

The photograph below show an example where cervical lesions recurred after the area was restored, in this case using porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns (PFM). In this situation it is clear that lesions are occurring at the gingival margin of the crowns and extending to the gingiva. When the crowns were originally placed, any lesions existing at that time were covered. These situations probably offer the best evidence for the length of time required for cervical lesions to form. Again, there has been no controlled data published in the literature, but patient recall of the time of placement of the restorations, suggests that a 10 year time lapse prior to recurrence may not be too far out of line.

If it only takes 10 years to form these lesions, why is it that younger patients tend not to have them? If a teenager starts working on some with diligence, will they not show up in his/her twenties? Truthfully, it is very hard to say! No one has collected the kind of data that will allow us to make a really informed decision, that is, statistically meaningful data is lacking.

Statistics notwithstanding, all dentists have noticed many cases where both new and recurrent lesions are obvious in older patients, but very few dentists have noticed definite lesions in patients younger than, say, 30 years of age. Again, you don’t get anywhere scientifically using words like “many” and “very few”, but these crude observations tend to at least qualitatively describe the situation as many see it.

When the lesions recur near a restoration, are there cases where the restorative material is obviously involved? Yes there are. I’ve seen cases where amalgam that was previously placed is showing definite signs of loss, and I have seen something similar for a gold foil restoration. Does this imply an abrasive cause in this case? Most people would think so. And yet, there are also cases observed where recurrent lesions form near apparently untouched restorative materials that are soft enough to be affected if direct abrasion were involved. One must always be alert to the possibility of multiple causes, and diagnose each case on its individual merits.

………. Moving Lesions

It is often observed that the cervical lesions have a kind of ragged or striated appearance upon close scrutiny with loupes. At first glance one can almost picture toothbrush bristles sliding back and forth in these “tracks”, but they are not parallel enough for this, and it’s hard to accept the same bristles in the same grooves year after year anyway. Sometimes we even see what appears to be several lesions that have occurred in the same area, probably where the active site of the lesions shifted periodically over the years. Sometimes it is observed that the active site seems to have at one time been more confined to the mesial side of the facial surface, but at other times was more pronounced toward the distal side, kind of like overlapping lesions. Keep this observation in mind for when we discuss possible explanations later.

Here is another observation which may be of interest … it is not unusual to see TWO such lesions on molars – one toward the mesial side of the surface and one toward the distal side. It is rather difficult to imagine how a toothbrush could cause both at the same time!

………. Facial versus Lingual Lesions

Almost all lesions that are clinically observed are on the facial surfaces, but sometimes lingual lesions are found. These are not readily explained by the brushing hypothesis! But, how can one explain the great preponderance of facial lesions in another way? Most people can and do brush much more on the facial surfaces than the lingual – does this imply that everything that happens more to the facial than lingual is caused by brushing? Certainly not. Later we’ll try to come up with an alternative explanation.

As an extension of this observation, there are times where there are clear cervical lesions, either on the facial or lingual, where the alignment of the teeth in the arch will not PERMIT the toothbrush to even touch the affected surface. In these cases it is clear that toothbrushing cannot be involved.

………. Shapes of Lesions

We have made another observation about cervical lesions – they tend to come in two shapes: saucer shaped and wedge shaped. The photos below shows the classic wedge shape. But we’ve already seen photo showing a “dished out” saucer or bowl shaped lesion. I’ve suggested they have different causes. Either type could show up mostly involving the enamel, or involving the dentin and enamel. So, the cause still COULD be similar, and it is the material structure of the tooth that determines the shape – but the most likely explanation is that they originate from two totally different causes.

Here are a few more clinical pictures of “wedge-shaped” lesions:

Causes of Non-carious Cervical Lesions

OK – now that we have studied these lesions a little, can we identify a cause? Is tooth brushing really the cause? Certainly NOT in some instances, especially when the toothbrush cannot even reach the affected surface of the tooth.

The literature on toothbrush abrasion goes back to the 1950s. The major work at the time found a correlation between the existence of lesions and the frequency of brushing and the abrasivity of the toothpaste. They also found a correlation with age, which is expected. One must note that there could be a completely different cause that would lead to a production of these lesions over time and that correlation with brushing might simply occur because older people in general tend to brush more and with the older, more abrasive pastes. This wasn’t checked in the study.

So, really, while some people probably do brush their teeth over-zealously, leading to some lesions, there is no convincing evidence that any major portion of these lesions have such a cause. In fact, in the 1950s the authors of that study never even considered the possibility of another cause!

The newest hypothesis for the cause of wedge-shaped non-carious cervical lesions is that they result from excessive pressure exerted on a particular tooth. The pressure can be due to habits like grinding or clenching. It is suggested that if pressure is applied to a tooth in a lateral direction when it is otherwise well supported by bone, THE TOOTH WILL BEND. This bending will give rise to a concentration of forces in the cervical region. These forces are thought to weaken the tooth material, either enamel or dentin (and even possibly a restorative material), resulting in breakdown.

The engineering term that applies to breakdown due to repeated flexure is ABFRACTION – and we often refer to these lesions in the mouth as abfraction lesions, IF they are wedge-shaped and not saucer shaped.

If you have a mailbox mounted on a pipe stuck in a concrete sidewalk, then you know about damage due to flexion. Open and close the box a few thousand times and the pipe will precipitously break very near the sidewalk. So you tooth breaks down near the bone – not a big surprise. This exact thing happened to my mailbox when I was in dental school.

But no one has proven whether flexion due to stress is the cause of cervical lesions. More and more dentists find it a reasonable concept, however, and we try to examine each case with both the brushing and flexion possibilities in mind. About 25 years ago I did measure tooth flexion in a living person’s mouth using miniature strain sensors – and while unpublished, it was convincing that teeth DO bend, not just TIP in the bone, but distort.

Some questions naturally arise. Some patients have ground their teeth absolutely “flat”, and sometimes this happens even to a young person. Many of these people, young and old, have no definite cervical lesions. The explanation may be that the wear was so violent and fast that the period of exertion of LATERAL forces was fairly short – just a few years. Also, once the teeth are ground nearly flat it is impossible to exert substantial lateral forces and thus to cause more bending of the teeth.

For people who have moderate grinding and clenching habits, such that lateral forces are strong BUT the teeth do not wear flat too quickly, cervical lesions seem to be more pronounced.

This field is subtle and not enough research has been done yet. Several groups are attempting to better understand the potential causes so that appropriate treatments may be made.

Also, when the teeth are not as firmly anchored in bone, as is the case with periodontal disease, the teeth under lateral loading will tend to TIP, rather than BEND. This means that for older people, typically, we don’t expect much formation of new abfraction lesions.

Research to show the cause of these lesions would involve actually measuring the flexure of the tooth surface. This is what I was referring to above, where a strain gauge was cemented to a tooth in a patient’s mouth, and demonstrated bending of the tooth during jaw movement. Note the picture below. But, it would need to be a more comprehensive, detailed study to prove the case.

Treatment of Non-Carious Cervical Lesions

The most common “treatment” for cervical lesions is to tell the patient to stop brushing so hard, or so back-and-forth, or with a hard brush. This is always good advice, but may have nothing to do with the problem. So a few years later the lesions are more severe and restorative measures must be taken. With more awareness in the dental schools over the last 20 years, there are more graduates that understand to some extent the likely nature of these lesions and can advise their patients correctly.

If tooth stress is the problem, then a reasonable preventive measure may be to wear a soft plastic nightguard during sleep. This will protect the teeth during nocturnal grinding which COULD be when the stress is highest. Another approach in single tooth cases is to attempt to find where on the tooth the force is being exerted (often revealed by a flat wear spot on the occlusal surface, and then to grind that area down so it won’t hit in lateral motion. But, eventually, another spot will come into contact and the process will start over.

When the cervical lesions are large enough to threaten the strength of the tooth, or when the area is sensitive to touch or cold, or when the lesions are approaching the pulp of the tooth, or when the appearance of that surface is not to the liking of the patient, the area must be restored in some way. For structural deficiency some material must be placed which replaces the lost tooth structure, or the tooth can have a “cap” or crown placed which covers the entire surface of the tooth. When the lesion is smaller but sensitive it may be that coating the area with a protective, penetrating substance will arrest the sensitivity. When encroaching on the pulp the lesion is restored to natural contour, as is the case of esthetic concerns.

The restoration of these lesions with a particular material should match the material to the cause of the lesion. If the tooth is undergoing considerable flexion, then the restoring material should be as flexible as the tooth, to minimize excess stress at the junction of the tooth and restorative material. The science in this area is still weak, however, and a variety of restorative techniques may be found in typical dental offices.

The bottom line is that we don’t really know what the cause of these lesions is, but the responsible dentist will look at both the brushing and flexion hypotheses in any particular case. Restoration should be done as appropriate for what the cause seems to be, and preventive treatment should correspond to any reasonable suspicion as to the cause.

Bottom Line for Noncarious Lesions

When we see decay, particularly on the facial side of teeth, it could be due to several causes. Broader lesions may be erosive, and caused by the acids of bitter (to most people) citrus fruits. Bowl-shaped lesions may be due to aggressive tooth brushing. Wedge-shaped lesions, which are BY FAR the most common, are likely due to bending forces applied to the teeth.

Most of the time, it is fairly easy to determine which are the causes of these noncarious (no decay) lesions, simply by looking at their shapes.

Restoration of Erosion lesions may be simply for esthetics – involving filling in the missing enamel with composite resin.

Restoring the Toothbrush lesion would be accomplished with the composite resin as well, but, typically these lesions are not as much of a cosmetic problem.

Restoring abfraction lesions would involve composite resin materials, but hopefully selecting those materials that have the flexibility to follow along with the deformations of the tooth itself.

Prevention in each of these three cases would involve: 1. Stop eating lemons; 2. Stop brushing so hard; 3. Find a way to keep from grinding to the side and exposing the teeth to lateral pressures.