You may want to supplement whatever you find in this site for the living tooth pulp and connection to bone by exploring a section on teeth in Wikipedia – they cover many important topics with good references to the literature in areas you may want to delve into more deeply.

Organization of this Chapter

You May Skip to Whatever Subject Interests You Now

Basics

The Pulp Chamber

The Canal System

The Roots – Curvature and Apex

Innervation and Vascularization

Odontoblasts and Immune System Cells

Periodontal Ligaments

Bottom Line for Living Teeth

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

The Basics

When the ENAMEL covering is made, it is made by cells on the OUTSIDE of the tooth, enamaloblasts. These cells are lost when the tooth erupts, for permanent teeth this starts at six years of age for the lower first molars. The DENTIN is formed by cells INSIDE the tooth, the odontoblasts. These cells are NOT lost at eruption.

The odontoblasts inside the tooth occupy the pulp chamber and canal system, and are nourished through the root apex. They have already made the normal amount and form of the dentin structure of the tooth before eruption, but can make more dentin throughout their life.

Odontoblasts will form more dentin INSIDE the tooth upon irritation – for example the acids of decay will irritate them through the remaining dentin and stimulate their formation of more dentin which in essence shrinks the pulp chamber away from the decay site by thickening the dentin in that area.

This is a vital mechanism whereby the tooth can protect itself from the inside upon invasion – and we will look in more detail at each of the physical parts of the tooth internally, as well as at the living cells involved.

OUTSIDE the root surface there is a cementum layer, which is made by living cells as well, the CEMENTOBLASTS, and they serve to maintain the connection of the tooth to the bone in a healthy manner.

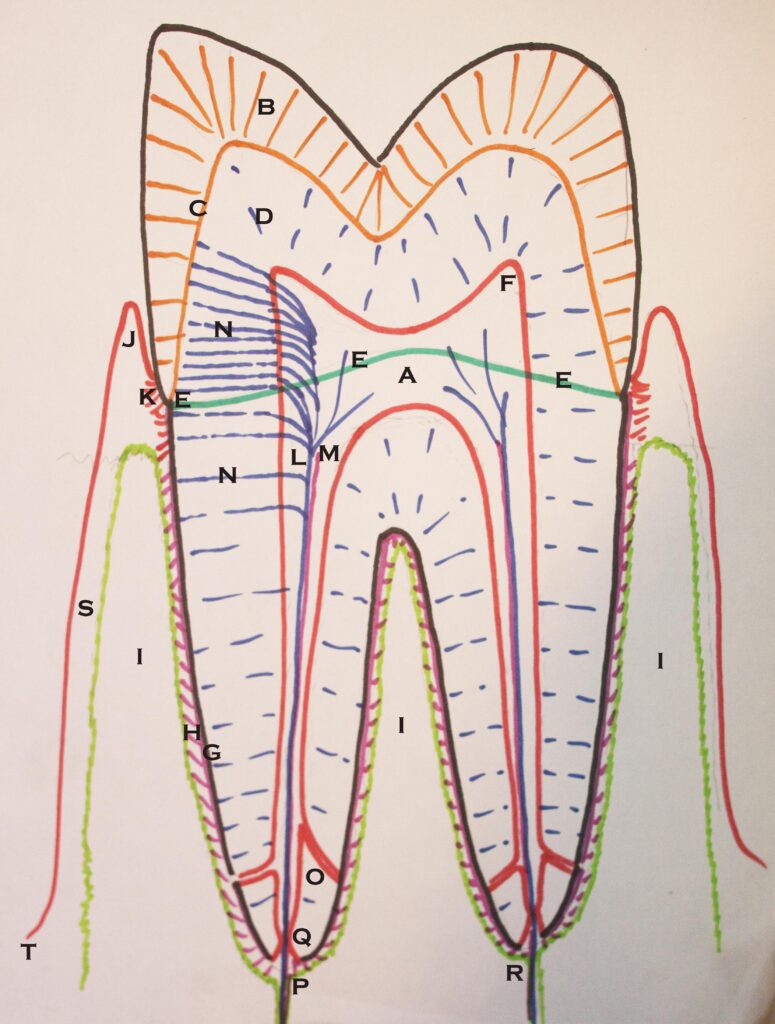

The diagram below illustrates all of the layers and more:

- A – The Pulp Chamber

- B – The Enamel Layer

- C – The connection between the enamel and dentin, the DEJ (dentinoenamel junction).

- D – The Dentin layer with small tubules penetrating from Pulp to DEJ and root surface

- E – The Cementoenamel Junction, CEJ.

- F – A pulp horn

- G – The Cementum Layer covering the root surface

- H – The Periodontal Ligaments which support the tooth by connecting the cementum to the bone

- I – The Alveolar Ridge of bone into which the root of the tooth inserts

- J – The Free Gingival Margin, separated from the tooth by a sulcus or pocket

- K – The Attachment Apparatus – where the gingival soft tissue connects to the tooth

- L – The Nerves that enter the tooth through the root and run through the dentinal tubules

- M – Vasculature in the pulp, coming in through the root apex with lymphatic vessels

- N – Nerves running through the dentinal tubules to the DEJ and root surface

- O – The terminal part of the root canal system, branching into an accessory canal

- P – The apical foramen at the end of the root where the canal enters/exits

- Q – The apical constriction near the apex of the root

- R – the terminus of the root – the geometric end of the root, and not necessarily where the canal exits

- S – The alveolar gingiva, connected to the bone of the alveolar ridge

- T – the mucosa, where the tissue leaves the connection to the bone and joins the tongue or cheek tissues.

The picture below shows a cross section of a human jaw – or mandible. The porosity of the bone, the root positions within the bone and the canal in the bone that conducts the nerve that enters all of the lower tooth roots, shows how these teeth are designed as living entities. Of course there are also blood vessels which enter the roots to support the living tissues in the pulp chamber, to be discussed below.

The Pulp Chamber

The pulp chamber mimics roughly the shape of the tooth on the outside of the crown of the tooth, where the enamel is found. For each of the cusps of the tooth the pulp chamber reaches a little higher as an extension we call a PULP HORN. The top of the pulp chamber is called the roof, and the bottom, appropriately, the floor. The floor of the pulp chamber is where there are openings, or orifices, that extend into the canals which follow the roots. Most of the living tooth-forming cells, the odontoblasts, are in the pulp chamber, but nourished through the roots.

Over time the pulp chamber will recede, extend less close to the surface of the tooth. This pulp recession may be simply caused by the passage of time, older people have smaller pulp chambers, or stimulated at a faster rate by the irritation of trauma (grinding teeth), or by decay acids. Sometimes the pulp chamber and canals as well become mineralized due to other processes not involving the odontoblasts, and this fills in the spaces so that the pulp chamber and root canals may be hard to see on an X-ray, and even difficult to find by exploration inside the tooth.

The mineralization or calcification of the root canal system marks the tooth giving up on life, and basically “boarding up” the place. A dead or necrotic pulp may not have a calcified canal system, but a calcified canal system may or not be necrotic. If a tooth is symptomatic or suspected of being necrotic, even if the canals are visibly calcified by X-ray, it is often necessary to explore the canal system, clean it out and open it up for filling. This is especially so if there is life detected in the tooth using an EPT – electric pulp tester. The dentist uses this device to check the VITALITY of the tooth by passing a weak current through the canal system and pulp. If it is calcified and yet tests vital, it may be the best choice to perform the root canal therapy (visit chapter V.10) to avoid pain in the future.

The Canal System

From the floor of the pulp chamber extend the root canals, following mostly the roots of the tooth. The major canals generally are quite centered on each root from the orifice in the pulp chamber to the tip of the apex. All canals, however, do not exit the exact apex of the root – they may deviate to one side and exit a mm or two away from the terminus. Also, some canals that leave the pulp chamber are notoriously difficult to see, their orifices are very tiny. If you are having a “root canal”, actually root canal therapy, RCT, done on an upper first molar, there is one root, the one toward the front of the mouth and the cheek (the MB root canal), which often contains two canals – MB1 and MB2. The second of these is the one which may or may not be there, or found. If it is there, but not found, then the RCT will often fail.

The root canals are likely to have ACCESSORY BRANCHES, which deviate to the side of the root. They are varied in location and size, and can typically not be seen on the X-ray, nor instrumented directly as the RCT is performed. There are most likely to be accessory branches in the bottom third of the root toward the apex, and these might actually be seen on the X-ray. If the nerve and vascular tissues in these accessory canals are not removed during the RCT, that can lead to failure – but this removal must be done chemically, and to fill the empty accessory canals requires pressure in that part of the canal which pushes sealer into the cleaned canals (see later).

The tooth is connected to the rest of the body through the root canal system. There are blood vessels, small arteries and veins, and lymphatic channels to drain excess fluid, and the sensory nerve which tells you when the vitality of the tooth is threatened, or something is compromising the dentin of the tooth.

The Roots – Curvature and Apex

The importance of the root form becomes most apparent when the dentist needs to clean out the infected or dead root canal system. If the root is very curved, more than usual, then it is increasingly difficult to REACH INTO the canal with an instrument. It also becomes far more complex to fill the root canal using the more traditional methods. Most roots are, however, relatively straight and some quite so.

Also, the root canal following each of the roots will normally have a taper which means that the canal is smaller in diameter as the root gets smaller in diameter. Dentists will then use tapered files which match the canal taper as much as possible when cleaning out a canal.

The location of the apex of each root, where the nerve and vascular channels enter the root, will be close to a tunnel-like channel running through the bone. Branches of the blood vessels and nerves come off for each root of each tooth, again, entering into the root canal system at a point at or near the apex or terminus of the root, but through an opening called a FORAMEN. At the foramen there is a little broadening of the canal as it approaches the surface, so that the vessels and nerve have a funnel-like shape to enter, but a constriction at the foramen itself.

If the root is fairly straight, and the foramen at the apex of the root, the dentist will have the easiest time performing any root canal therapy that is needed. Otherwise, the shape can be challenging enough so that a specialist in root canal therapy may be required to perform the task. Dentists will often refer this work to the endodontist for this reason.

Innervation and Vascularization

We already know about the entrance of the nerves and vessels into the tooth through the apical foramen, but we need to discuss a little more about where they go from there. As we discussed DENTIN earlier, the microstructure of the dentin was not covered in much detail. It is the presence of the nerves in the tooth that makes an understanding of this dentin structure important.

Dentin is filled with TUBULES. These are little microscopic channels or tunnels, which extend from the pulp chamber to the junction between the dentin and enamel – the DEJ. They all extend outward basically perpendicular to the inner surface of the pulp chamber and, as well, perpendicular to the enamel. These tubules stop very near the DEJ.

Each of the tubules contains a branch of the nerve which enters the tooth through the root! There are literally millions of little nerve extensions reaching through the dentin to let you know, in no uncertain terms, whether there is some kind of irritant near the DEJ, presumably having already eroded its way through the enamel. The enamel has NO nerves – it is just the inert, protective covering outside the dentin.

So, the innervation of the tooth is designed as an early warning of attack to the tooth, and the vascular content of the pulp chamber provides nourishment for the odontoblasts, which wall off areas from which this attack is coming.

Odontoblasts and Immune System Cells

While these have been alluded to previously in this section, these cells are the only remaining cells which form any part of the tooth, and they can continue to form dentin from inside the pulp chamber as long as they are kept healthy. They are kept healthy as long as the blood and lymphatic channels which enter the tooth are kept viable. Sometimes, if there is damage to the vessels entering the root of the tooth, due, perhaps to some kind of trauma, the flow is interrupted and everything within the tooth dies.

The tooth also has immune cells within it, but they are not particularly effective, or they just take their time about it. The problem is that when there is an infection in any other part of the body (other than the head), the immune system can immediately react and get the appropriate cells of the immune response there quickly. Also, since the early response is inflammation with the ensuing swelling, we have a problem in the tooth (and the skull) as the space is confined by a rigid shell which increases pressure and pain.

For the part of the immune response that utilizes immunoglobulins, the constricted communication between the body and the tooth definitely compromises how effectively the tooth pulp can fight off infection.

Periodontal Ligaments

While the area AROUND the roots in the bone is not technically part of the tooth, it is an important living part of the body which relates very much to the tooth.

As the tooth roots are embedded in the bone, it represents a juxtaposition of two hard tissues, but they don’t simply touch root to bone – there is a cushioning layer between. We call this space between the bone and the tooth root the PERIODONTAL LIGAMENT LAYER – PDL. This is quite a remarkable area, in fact, for, as with muscle attachment to bone with tendons, there are collagen fibers (periodontal ligaments) here which somehow JOIN into the substance of the hard tissues on each side of the space. On the tooth side of the PDL is the CEMENTUM layer which covers the dentin of the root. The cementum layer is thin, but it provides an organic fiber scaffold for the mineralization of the cementum that is compatible with the organic collagen fibers of the periodontal ligaments.

On the bone side of the PDL, the organic molecular scaffold upon which the bone mineralizes is compatible with the collagen fibers of the periodontal ligaments.

In essence, the fibrous scaffolds of the bone and cementum extend into the PDL space AS the periodontal ligaments – forming one continuous fibrous network supporting the tooth roots in the bone. This is why the teeth are slightly mobile in the bone – if you push on them with some force, you can actually see them tilt a little away from the pressure as the fibers are stretched on one side and compressed on the other.

Now, within the PDL space, there are living cells, just as there were in the tooth pulp. There are CEMENTOBLASTS and OSTEOBLASTS. There are also OSTEOCLASTS! What are these?!

A cementoblast can make more of the cementum layer on the outside of the root. To do this also involves forming the organic fibrous protein network that connects to the periodontal ligaments. Sometimes, a patient may have hypercementosis, which is making TOO thick a layer on the outside of the root (making extraction, where necessary, VERY difficult). But normally, the cementum layer and intermingled ligamentous fibers are well maintained.

The osteoblast forms bone, along with the scaffold of supporting fibers, and the osteoCLAST erodes bone – takes it away. These two cells are stimulated by forces transmitted along the periodontal ligament fibers! AND by forces NOT transmitted along the fibers.

Picture the orthodontist who has put a bracket on the tooth and a wire through that bracket that is pushing the tooth in a particular direction. The pressure on the tooth, as long as it is not too much pressure, causes the osteoclasts on the side of the tooth toward which it is being pushed to ERODE BONE, while the osteoblasts on the side of the tooth away from which it is being pulled, to make MORE bone. In this way, the tooth will move because the socket for the roots is changing position. When the pressure stops and the tooth sits in one place for long enough, the bone fills in completely on both sides and the tooth is stable again.

When there is NO pressure on a tooth which is transmitted to the bone, perhaps because there is NO tooth, the bone will spontaneously erode – the osteoclasts will reduce the bone level in the alveolar ridge because it is no longer needed to hold teeth.

It is the pressure of the teeth against the bone which maintains the height of the alveolar ridges in our mouth. These ridges will resorb, particularly the lower one, when a patient is wearing dentures and has no teeth to transmit the forces INTO the bone. On the other hand, IMPLANTS can also maintain the level of the alveolar ridge because they conduct forces into the bone from the occlusal pressure on the crowns on the implants. Implants do NOT have periodontal ligaments or a PDL, but the forces transmitted are nonetheless effective in keeping the bone eroding and forming at a balanced level.

Bottom Line for Living Teeth

In reality, you can see that every structure in the mouth is alive. The bone, the periodontal tissues, and the teeth are all alive. There are many cell types that are responsible for the REMODELING of the bone (erosion and formation), and for the formation of dentin and cementum, as well as providing immune functions and sensation in all of the tissues.

So, not only is the mouth a complicated place in its basic design – the most complicated place in the body – it has been built to change with time and as a response to stimuli. The dentist must find a way to intrude in this process so that corrections can be made without compromising the natural, living, relationships within the mouth.